The War of Black and White

The White Tribe’s lord, Mili Dongzhu, lived in the land of white sky and white earth, while the Black Tribe’s lord, Mili Shuzhu, occupied the land of black sky and black earth. The two sides became enemies over a sacred tree by the divine sea of Milidaji. Shuzhu stole the sun and moon from the White Tribe, sparking a war. Dongzhu’s son, Alu, defeated the Black Tribe multiple times, but was ultimately captured and sacrificed after falling for a beauty trap set by Shuzhu’s daughter, Cimu. After Alu’s son returned to deliver the news, Dongzhu, with the help of celestial warriors, finally crushed the Black Tribe, allowing light to remain forever in the human world.

Story

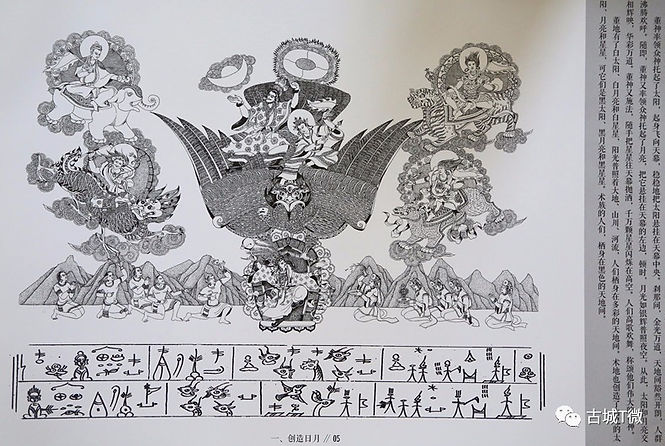

“The War of Black and White” (also known as “The War of Mang and Shu”) is a mythical epic battle between two opposing forces: the Mang side (White side) and the Shu side (Black side), representing two tribes—the Mang tribe, associated with daylight, white sun, and bright lands, and the Shu tribe, linked to darkness, black earth, and the black sun.

The war began when Aisen Miwen, leader of the Mang tribe, sought to create a more perfect world. To do so, he hired Dongruo Walu, a brilliant creator from the Shu tribe, to help him forge new celestial bodies and reshape the heavens and earth. However, Mili Dongzi, leader of the Shu tribe, feared that the light of the Mang tribe would disrupt the balance of the Shu realm. He set a trap, falsely accused Dongruo Walu of committing a “demonic sin of the black land,” executed him, and shifted the blame onto the Mang tribe.

Enraged upon learning the truth, Aisen Miwen sent troops to punish the Shu side, but they were defeated. The Shu side then dispatched the beautiful Geru to seduce Dongruo Walu. Gradually letting down his guard during his experiments, Dongruo Walu was eventually ensnared by the trap of affection and perished.

His death ignited a full-scale war between Mili Dongzi and the Mang tribe. Despite their efforts, the Mang side was unable to overcome the fortified defenses of the Shu tribe—until the Sky God Duoge Yuma descended with 360 war deities, helping the Mang side shatter the Shu fortress and claim final victory.

In the end, the mountains that once marked the boundary between black and white vanished, and the two sides transitioned from opposition to integration. The Mang people lived in the white lands, the Shu people remained in the dark realm, and the world was unified in peace and harmony.

Spiritual Foundation

Although The War Between Black and White is a mythological epic centered on conflict, its core message conveys a spirit of peace and reconciliation. The clash does not culminate in total destruction born of hatred, but rather in restraint during confrontation and eventual integration. As pointed out by Dongba culture scholar Master He He Zhenwei, while the war was triggered by Mang side’s creator Dongruowalu breaking conventional norms, the Shu side’s attempt to completely erase the Mang people also calls for reflection. Just as in real life a child who errs should not be met with irreversible punishment, in the end, the heavenly deities chose to support the Mang side and retaliate against the Shu side. This shift reflects the central tenets of Dongba culture—“harmony in diversity” and “unity between heaven and humanity”—which advocate for a peaceful coexistence between humans and nature rather than mutual destruction.

In the Dongba mythological system, the “Shu side” often symbolizes nature itself (also called “Shu”), while the “Mang side” represents humanity. Like half-brothers, the peaceful relationship between them serves as a metaphor for the ideal harmony between humankind and the natural world. Thus, the conclusion of The War Between Black and White does not depict total annihilation, but rather the blending of black and white and the restoration of balance, embodying the profound influence of this philosophical worldview.

From a broader perspective, though history is often marked by the brutality of war, war has also served as a catalyst for the exchange and fusion of civilizations. Whether it was Alexander the Great’s eastern campaign or Genghis Khan’s western conquests, such events led to the collision and intertwining of cultures. The same holds true in the remote mountains of southwest China: the Dongba culture of the Naxi people was gradually shaped through prolonged interaction with the Bai, Lisu, Tibetan, and Han ethnic groups. This pattern of multiethnic coexistence and continuous cultural exchange reflects not only the inclusiveness and peaceful tradition of the Chinese people but also sustains the vitality of these cultures today—distinct from many parts of the world where ethnic histories are marked by sharp divisions.

Therefore, when engaging in artistic or cultural interpretation of The War Between Black and White, the focus should go beyond surface-level conflict and destruction. Instead, greater emphasis should be placed on themes of integration following conflict, reconciliation between humans and nature, and the vitality and warmth that emerge from cultural fusion.